The Chinese Student Workload Reduction Act: An Analysis of its Effects

I sigh as I wrote down the answer to Question 103 of the maths assignment, letting my pencil land on the table with a thud as I limp out of the dark room lit by a single desk lamp, getting ready for the daily 6 hours of sleep. Tomorrow, the alarm will wake me up at 5:30, beginning another day of lectures, tedious study hours and a mound of worksheets. This draining cycle of monotony will continue for at least the next 6 years.

In 2021, nine Chinese government departments jointly issued a decree, aiming to “comprehensively and systematically promote the work of reducing the workload of primary and middle school students”, resulting in “specific implementation plans from 24 provinces”, according to Xinhua News. Following this decree, schools were banned from conducting course placement exams and publishing class rankings, and all extracurricular educational institutions were forced to close down. This was immediately met with great reception, receiving support from education professionals, parents and students alike. It was understood as a step in the right direction to promote a more holistic education, develop soft skills like independent learning and critical thinking, and, most importantly, to reduce the stress of a generation of overworked students.

However, this could not be further from the reality. To start, the “banned” extracurricular institutions simply continued with a different form. The shortened school hours exacerbate this issue, as students do not learn as much in class, a gap that can only, for most families, be made up by sending students to the above-mentioned institutions. These institutions are expensive, take up a lot of hours, and, as they are technically not restricted by the workload reduction decree, are allowed to set as much work as they want to, causing students to be even more overworked and stressed-out.

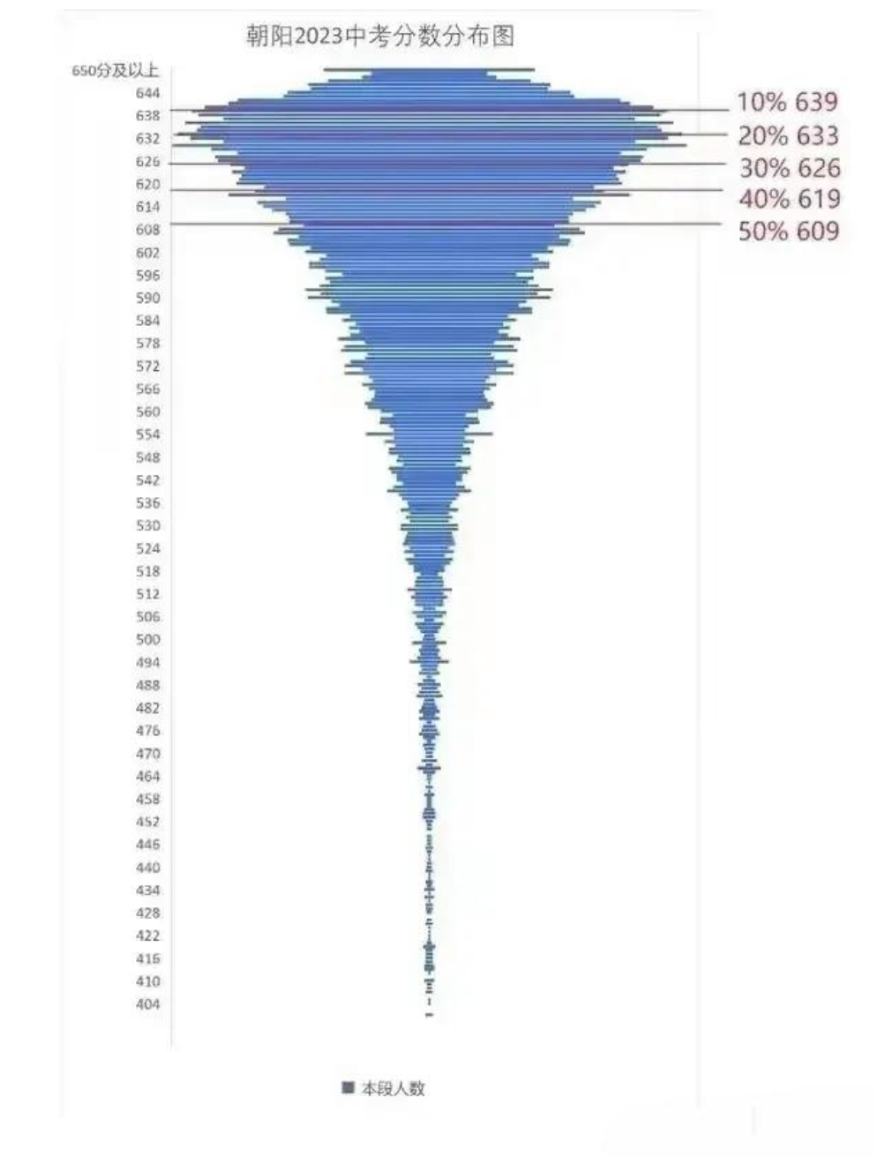

As school classes and exams become easier, a unique case of exam score “inflation” occurs. Before the policy change, exam scores in China generally follow the Normal Distribution Curve, with most students scoring in the range of 70% - 80%. About 10% of students score more than 90%, and an even fewer number scoring a full mark. However, after the exams became easier, almost everyone scores more than 95%. For example, in the 2023 High School Entrance Examination, 40% of students in Beijing scored more than 619 out of the possible 650 points.

PICTURE: the 2023 High School Entrance Examination scores of Beijing’s Chaoyang District display a frightening mushroom cloud shape, with most of the students extremely close to achieving a perfect score.

This inflation causes unnecessary stress and tension in Chinese families as parents continuously raise their standards for children: “If you only score 5 more marks, you’ll get a perfect score!” “If you didn’t miss that 1 Multiple Choice, you’ll be Top 10 in your class!” This zealous chase of the perfect score in a very close competition rips families apart and often pushes students to the edge.

Mr. Xiao-Bing Yu, a well-known Chinese high school teacher, revealed in an article that this state of seemingly aiming for perfection is in reality “morbid and ignorant”, as he states his 3 reasons:

To achieve a higher score, a student will need to revise not only for the main concepts covered, but also various minor details, which requires a lot of time and energy to memorise. For instance, it requires on average 2 hours of study time to improve one’s score from 80% to 85%. To increase their score by another 5%, they will need to study for 3 or 4 hours. To increase by yet another 5% will take more than double the time, while this will probably not even be enough to achieve full marks. The time invested will be used for repetition and memorisation of minor details, which does not count much towards increasing a student’s knowledge and skills.

Repetition to increase exam scores will easily make students lose interest. Passion for a certain area of study will only be kindled by the attraction and curiosity of the unknown, instead of a robotic repetition of the known. As a result, once today’s students, who spend most of their times doing repetitions for higher exam scores, graduate and, therefore, move away from the stimuli of exams, they will struggle to find purpose and feel at loss in life. This hollowness of the soul and lack of self-worth can cause an array of issues for the next generation of adults.

Pursuing the “perfect answer” is, to an extent, a lower-level skill. Chinese exams focus on multiple-choice questions and analysis with the goal of students composing an answer that fits with the single, “standard” marking criteria. If one’s opinion is different from the opinion conveyed in the marking criteria, the student’s answer will be considered wrong. However, it can be recognised that the world is not black-and-white: instead, it’s a complex matrix of diverse ideas and opinions, and creativity, critical thinking and acts of questioning authorities that drive progress stem from this complexity. Standardised tests, in contrast, discourages students from developing these abilities.

Unfortunately, not everyone in China agrees with Mr. Yu. In this rat-race to the admission of elite high schools and universities, parents fervently sign children up for more and more classes to make up for a school education that lacks rigour in an attempt to out-compete their children’s peers. Arts and sports courses make way for exam preparation, students get more work from parents, peers and extracurricular institutions, and as students get higher and higher marks, the margin of mistakes become small, which lead to more pressure on students to spend more hours on repetition and revision. And as everyone follows this trend, the Workload Reduction Act ironically achieves the opposite of its original goal.

REFERENCES

Sohu.com (2018) The Voice of a Top Teacher: The Fanatical Pursuit of Higher Scores is Morbid and Ignorant; Consistently Scoring More Than 80% in Tests is Enough Available at: https://www.sohu.com/a/219032127_385655#google_vignette (Accessed: 20 August 2023)

Xinhua News (2019) Student Workload Reduction Makes Parents Anxious; Ministry of Education: “One-Size-Fits-All” is Impractical Available at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2019-11/15/c_1125233976.htm (Accessed: 20 August 2023)